First in a series

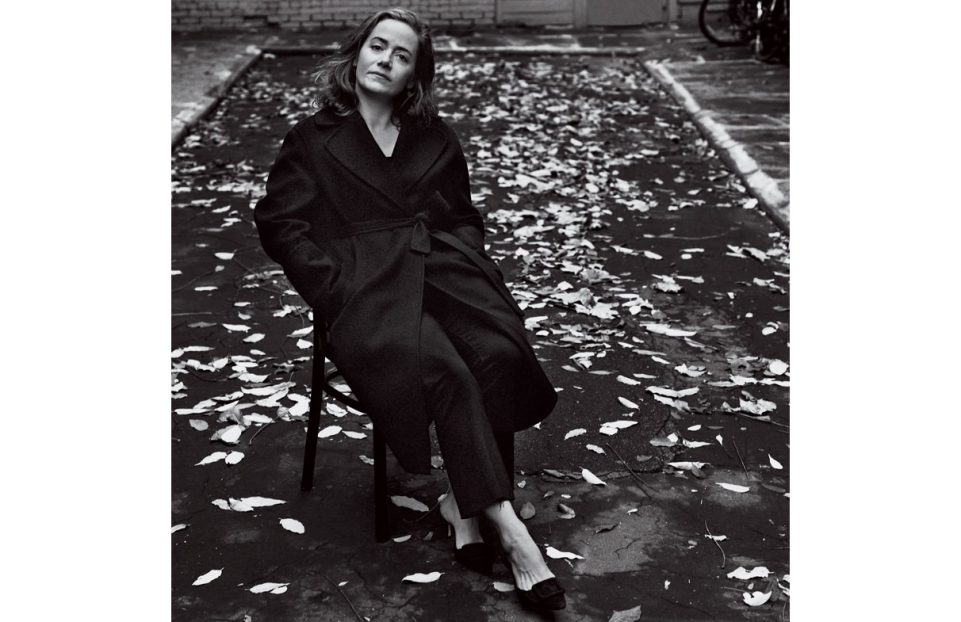

Director and producer Mimi O’Donnell focused on her three children when they lost their father, Philip Seymour Hoffman, four years ago.

The first time I met Phil, there was instant chemistry between us. It was the spring of 1999, and he was interviewing me to be the costume designer for a play he was directing—his first—for the Labyrinth Theater Company, In Arabia We’d All Be Kings. Even though I’d spent the five years since moving to New York designing costumes for Off-Broadway plays and had just been hired by Saturday Night Live, I was nervous, because I was in awe of his talent.

I’d seen him in Boogie Nights and Happiness, and he blew me out of the water with his willingness to make himself so vulnerable and to play screwed-up characters with such honesty and heart.

I remember walking into the interview and anxiously handing Phil my résumé. He studied it for a few moments, then looked up at me and, with complete sincerity and admiration, said, “You have more credits than I do.”

I felt myself relax. He wanted to put me at ease and let me know that we would be working together as equals.

After the meeting, I called my sister on one of those hilariously giant cell phones of the time, and after I had raved about Phil, she announced, “You’re going to marry him.”

Working with Phil felt seamless—our instincts were so similar, and we always seemed to be in sync. Though there was clearly a personal attraction, both of us were involved with other people, so we fell in love artistically first. Over the next two years, we continued to work together—I designed the costumes for everything he directed—and, along the way, I was invited to become a company member of Labyrinth, of which Phil was the artistic director.

As an ensemble, we produced Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train, which put us on the map. Then, seven years to the day since I’d moved to the city, 9/11 happened. It was disorienting to be finding our place as the world seemed to be collapsing around us.

When Phil and I weren’t collaborating, we would see each other at meetings, readings, rehearsals, or any number of the endless parties the company threw. It was a fertile, exciting time—we were all young, at our best and healthiest, and we were all in love with theatre and with one another.

‘I Hope He Is There’

Before every event, I’d think, Oh, God, I hope Phil’s there. And if he wasn’t, I was disappointed. It wasn’t so much that I wanted to date him. It was that I thought, You’re so attractive on every level that I want to be near you as much as I can.

In the late fall of 2001, we both found ourselves single, and I heard that Phil had been asking around about whether I had a boyfriend. He invited me to dinner at a little Italian restaurant in the East Village.

Afterward we went to a tiny gallery nearby and looked at photographs taken on 9/11. I think what was going on in both our heads was: Do we feel this way outside work?

And it instantly became clear that we did.

But we were cautious. It felt all-encompassing. I loved working with Phil, and I was falling in love with him, and I didn’t want to lose the experience of being his collaborator if we broke up.

After our second or third date, I said to Phil, “I don’t want to just see you casually and see other people. I want to be with you.” He immediately said, “Yeah, I’m all in.” One afternoon not long after that, we were walking in the West Village and ran into a couple we knew.

Candid About His Problems

As we stood talking, their four-year-old son started riding his scooter off the curb toward the traffic. Without missing a beat, Phil reached out and with his big, beautiful hands guided him back onto the sidewalk, patted him on the head, and said, “You’re good, buddy.” It was gentle, it was firm, it was kind. At that moment I thought, I’m having children with this man. It was a done deal.

From the beginning, Phil was very frank about his addictions. He told me about his period of heavy drinking and experimenting with heroin in his early 20s, and his first rehab at 22. He was in therapy and AA, and most of his friends were in the program.

Being sober and a recovering addict was, along with acting and directing, very much the focus of his life. But he was aware that just because he was clean didn’t mean the addiction had gone away.

He was being honest for me—This is who I am—but also to protect himself. He told me that, as much as he loved me, if I used drugs it would be a deal breaker. That wasn’t an issue for me, and I was happy not to drink, either. Phil was so open about it all that I wasn’t worried.

A New Year’s Eve date made things feel official. Phil was looking for a new apartment and asked me to come along. One day in the spring, I told him that I wasn’t going to renew my birth control prescription.

He simply said, “Good. Don’t.”

I was 34, which felt old at the time.

(To be continued)

This series originated at www.vogue.com